Elvis Presley’s story might be unfilmable—an odd thing to say about someone who’s probably one of the most filmed human beings in history. This is in part because Elvis himself is not actually very interesting—it’s what happened to Elvis that’s enormously interesting. This is a distinction that popular entertainment isn’t usually that well-equipped to handle, which is one reason why so many such explorations of Elvis—biopics and miniseries that attempt to illuminate or otherwise “explain” him—are so forgettable. Who really was Elvis Presley? Few people have ever truly known, and I’m not sure how many have even truly cared. Elvis has always been what we make of him.

The latest entry in the Elvis-making canon is Baz Luhrmann’s cacophonous, fitfully entertaining, and mostly pointless Elvis. Like much of Luhrmann’s work, Elvis is a hyperactive, showy, and gleefully un-subtle affair. Elvis’ Elvis is played by Austin Butler, who does his best with the script he’s given and admirably avoids the pitfalls of impersonation, but whose naturalistic and introspective approach to the role never quite jibes with the garish, near-hallucinatory world of the film.

Elvis has little new to say about its title subject, and its ostensible fix for this is to make Elvis the main character in someone else’s story. Here that someone is Elvis’ longtime manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker, a renowned scumbag who, as music-biz scumbags go, isn’t even all that exceptional. (See: rule No. 4080.) By all accounts Parker the man wasn’t particularly curious about music, the world around him, or even Elvis himself, at least anywhere past the capacity of these things to make him lots of money. If your movie’s claim to novelty is exploring Tom Parker’s perspective on Elvis and his life and times, chances are you’ve already messed up.

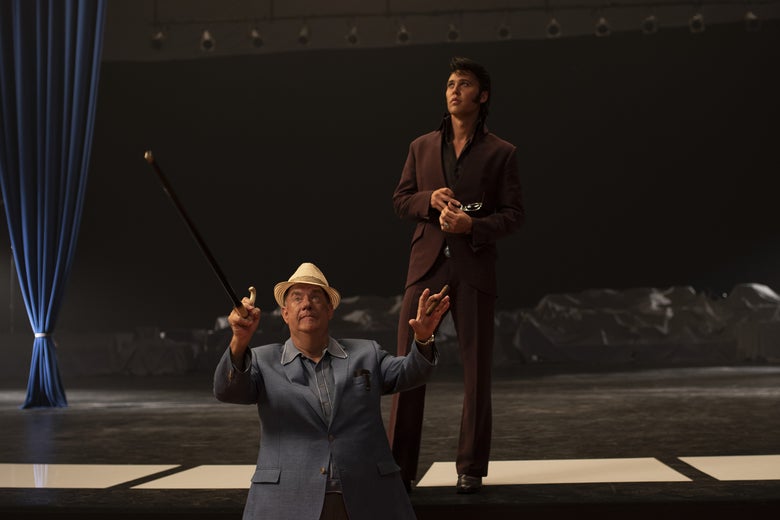

It doesn’t help that Parker is played by a disastrously miscast Tom Hanks, whose grotesque facial prosthetics and bizarre accent frequently made me wonder if I was watching the first-ever acting performance inspired by Watto from the Star Wars prequels. The movie leans hard into Parker’s background as a carnival worker, where he first learned to embrace the role of the “snow man” who performs “snow jobs” on delighted audiences. (The film repeats these phrases so incessantly that it seems to assume you’re not paying attention.) From Parker’s early narration we’re meant to gather that Presley was the Colonel’s “snow job” par excellence, a strange conceit from which to introduce all the hagiography that’s to follow. Are we supposed to believe that Elvis was some once-in-a-century musical visionary, or a canny fraud perpetrated on a world full of rubes? Most reasonable music fans would probably argue that the answer is neither; Luhrmann’s film seems to suggest that it’s somehow both.

In its first hour or so, the movie gamely hits all of the familiar beats of Presliography: the staggering early Sun sessions, the subsequent contract with RCA, the scandalous television performances, the military conscription, the death of Elvis’ beloved mother. This period of Elvis’ life is far and away the most interesting—indeed, this period of Elvis’ life is the reason he remains one of the most famous people of the 20th century—but the movie oddly rushes through it, as though it has somewhere else it needs to be. Conversely, an inexplicable surplus of time is spent on Elvis’ 1968 “Comeback Special” which the film seems intent on depicting as some sort of career pinnacle, a silly attempt to insinuate Elvis into the late-1960s counterculture.

Then we’re back to fast-forward mode. Mere minutes after the triumphant special, Elvis learns about both Altamont and the Manson Family murders and is introduced to the infamous Dr. Nick, all in the same scene. That’s an awful lot to drop on poor Elvis, and things only go downhill from there. Drugs are taken, marriages collapse, guns are wielded, more drugs are taken. Through it all, the show must go on. When Elvis (allegedly) dies at the film’s end, we’re subjected to the Colonel warbling at the audience that what really killed him was “his love for you,” a half-assed turn toward messianism that comes at the audience’s own expense. Leave me out of this, Watto!

The frantic, kitchen-sink nature of all of this lends an overarching glibness to the film, which is almost an impressive feat given its 159-minute running time. In particular, the movie’s approach to race—surely the most controversial and forever unsettled aspect of Elvis’ legacy—is gallingly obtuse. Black characters exist as props whose primary function is to vouch for Elvis’ own mythic racial transcendence: The famous photo of a young Elvis standing arm-in-arm with a young B.B. King practically receives its own subplot, and Elvis’ oft-cited 1969 remark about Fats Domino being the real “King of Rock ’n’ Roll” shows up only as testament to the white singer’s humble generosity. The movie’s depictions of Black music-making often feel flagrantly racist, shot after leering shot of carnal, frenetic ecstasy, while whole traditions like gospel, blues, and R&B are reduced to raw material for Elvis to bring forth to benighted white masses. One especially strange scene features Elvis fleeing hordes of fans to catch Little Richard performing “Tutti Frutti” in a small club in Memphis, an encounter the movie depicts as a moment of Promethean discovery for Elvis. But “Tutti Frutti” was already a national hit before Elvis had even released a single on RCA; many Americans, white and Black, had heard Little Richard before they’d ever heard Elvis Presley.

[Read: HBO’s Admirable New Elvis Documentary Would Have Benefited From More Suspicious Minds.]

Since he first rocketed to fame, Elvis has often been cast as an allegory for things much larger than himself: for the social revolution of rock ’n’ roll, for newly dangerous modes of adolescent sexuality, for the white expropriation of Black culture, for a particularly American imagining of self-making and self-destruction, to name just a few. In life and death, he was trapped between symbol and symptom, an endlessly refreshable canvas for what other people want to think about him, themselves, and others. Much of the very best writing about Elvis—from Greil Marcus to Lester Bangs to Alice Walker—has started from this premise, that the “there” there was never as much about Elvis as it was about everyone else.

In some ways this very blankness would seem to lend itself to a director like Luhrmann, whose movies have always been fascinated with surfaces and rarely been particularly interested in multi-dimensional people. It’s odd, then, that Elvis’ most flummoxing flaw is an inclination towards a sort of characterological moralism. For all the feedback-drenched electric guitars and trap-inspired 808s on the film’s soundtrack, the most anachronistic element of Elvis is its cloying need to assure us that its hero was a good person, as if trying to preemptively counter some imagined onslaught of TikToks about why Elvis Presley is problematic. The movie goes to pains to depict Elvis as a man of liberal conscience who is deeply moved by the various political and social crises facing the United States in his lifetime but whose activist inclinations are repeatedly thwarted by the dastardly Parker. (The film studiously avoids any whiff of the later-in-life Presley’s obsessions with law-and-order conservatism.)

What Elvis really thought about the issues of his day is largely unknowable. He almost never spoke about such things publicly, and stories of views he expressed in private have mostly come from people with an investment in making Elvis appear a certain way. I don’t pretend to know what was in Elvis’ heart; even just writing that feels ridiculous. But I also don’t think it really matters, and any serious consideration of Elvis as an artist needs to be comfortable with that. What mattered about Elvis was his music, particularly a bunch of recordings that he made between 1954 and 1958 that, to no small degree, changed the world. That music’s legacy is as formidable as it is complicated, but Elvis is too frantic and insecure to reckon with that complexity. Instead we’re left with a deceptively conventional and conservative biopic whose sleights of hand can never quite distract from a core that’s cold and pale. It’s a snow job.