In Chicago it’s simply the map.

No matter what kind of data you’re looking at, the city’s infamous segregation produces the same results: One thing on the prosperous North Side, another on the poor South and West sides.

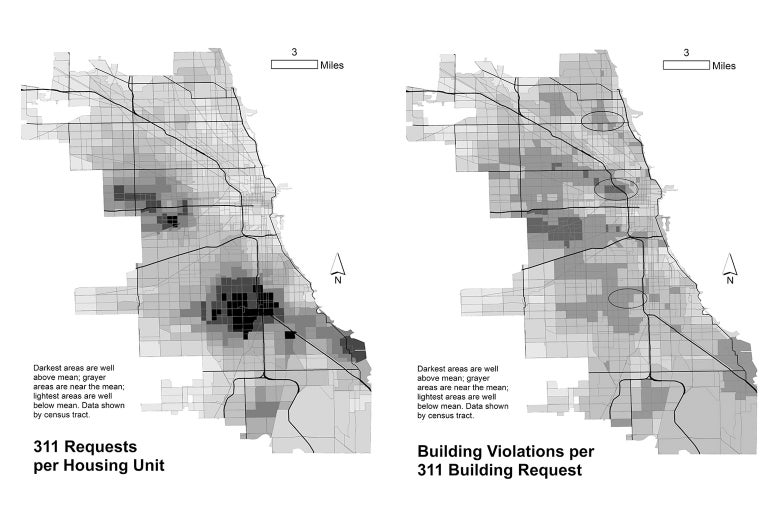

So it went when the Tulane sociologist Robin Bartram plotted out how many times Chicagoans called 311 to complain about building violations such as lack of heat, broken windows, unkempt yards, and rats. The city’s South and West sides light up. No surprise that housing conditions associated with poverty would be concentrated in the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

But then Bartram discovered something that defied the intractable Chicago map. She expected building inspectors to follow through with enforcement, leading to fines, court dates, and foreclosure—a cycle of self-reinforcing poverty that’s a common result of revenue-driven enforcement. “That’s the book I thought I was going to end up writing,” Bartram told me recently. “I had assumptions based on conventional wisdom about how people like building inspectors and police persistently end up punishing low-income people and communities of color.” This pattern is true, for example, of how the Chicago police issue tickets to cyclists: mostly in Black and brown neighborhoods.

But with building problems, the pattern turned out to be the opposite: Inspectors doled out violations fairly evenly, in spite of where 311 calls were concentrated. They issued more violations in high-income areas than low ones, and more violations to owners of large buildings than small ones.

“When inspectors turn up at homes in low-income communities,” Bartam writes in Stacked Decks, her study of Chicago inspectors based on 10 years of data and months embedded in city’s Department of Buildings, “they are less likely to cite buildings for code violations than they are to cite buildings in areas with higher incomes. … Inspectors are a group of mostly White working-class men who grew up in White ethnic enclaves famous for racism. Yet they make efforts to help out low-and moderate-income property owners and landlords in communities of color who struggle to maintain their buildings.”

In other words, Bartram argues, building inspectors have a kind of working-class solidarity that comes through in their resentment of negligence, profiteering, and corporate landlords. Some code violations are cut-and-dry—such as the heat not working, a common tenant complaint in Chicago. But 60 percent of violations require a judgment call, and here, building inspectors exercise a lot of discretion about who needs to be punished and who deserves some slack.

You could read this another way, of course: You could argue that building inspectors take complaints in the city’s high-income neighborhoods more seriously, and leave tenants in poor neighborhoods to suffer through substandard housing conditions. Indeed, a result of this selective enforcement is higher standards for housing upkeep in higher-income neighborhoods.

But based on interviews and fieldwork with the inspectors, Bartram has come to the conclusion that the building inspectors see themselves as fighting for the little guy. They’re trying to use their small authority to right the wrongs of a highly unequal city—and that means not peppering the city’s poorer neighborhoods with fines and court dates. “They try to protect property owners in communities of color,” she writes.

They operate in the long tradition of American housing reform, which has struggled since its inception to strike a balance between insisting on better conditions for the poor without regulating all low-income housing out of existence. This is not an abstract question for building inspectors. Landlords are not allowed to evict tenants over complaints, but the city can force significant renovations that wind up capitalized into higher rent—if they don’t require the building to be vacated immediately. The trade-off is particularly fraught right now, since the federal government has stepped back from its role helping low-income Americans keep a roof over their heads.

Why do building inspectors, in contrast to most public officials—notably the police—let poor neighborhoods off easy and crack down on fancy ones? Many of these professionals have roots in both the impoverished Chicago bungalow belt and in contracting, Bartram observes, which gives them a sympathetic eye to the maintenance of the city’s single-family homes, two-flats, and three-flats. (Chicago is different from many American cities in this respect—its lowest-density neighborhoods are also its poorest.)

In Bartram’s view, the inspectors’ sense of the city’s social geography is also informed by their travels: They see the inside and outside of everything from condo construction in gentrifying neighborhoods to bug-ridden slums. I would add one more reason for the inspectors’ race-blind sense of class consciousness that belies some other research about implicit racism: They spend most of their time looking at buildings. When they see a sagging porch or a broken window, they rarely see the person responsible for it.

Which brings us to a more difficult question: Is the housing inspector’s discretion a force for good? On the one hand, a more punitive approach would put greater stress on the city’s beleaguered Black homeowner class, whose numbers are already declining.

Then again, most 311 complaints are made by tenants. While Chicagoans love to lionize the stock of small rental buildings that provide the backbone of Chicago rental housing, it’s not clear how many of these buildings are owned by struggling mom ‘n’ pop landlords—and how many are the property of professional investors.

Unlike the small, quality-of-life offenses that are the target of “broken windows” policing, real-life broken windows (and other borderline building violations) demonstratively do create a cycle of decline if they’re not addressed. Inspectors are “caught in this Catch-22,” Bartram says. “Their compassion means that in certain places, the cycle of dilapidation continues. But coming down hard wouldn’t help either.”

Still, we can’t expect building inspectors to solve all Chicago’s problems. What they do, Bartram says, is try to be compassionate with the discretion that’s built into their jobs. We tend to associate that kind of discretion with high-level officials like judges, but it’s the work of low-level functionaries too, from the DMV to traffic cops to bus drivers. What stands out about the building inspectors is not that they make choices about how to enforce the rules—everyone does that. Unlike other functionaries, however, they do routinely confront the downstream consequences of their choices, as a building falls into foreclosure—or upcycles away from affordability.