Anytime Rachel Paula Abrahamson needed to include a celebrity’s weight for a diet story at Us Weekly, she knew to call Dr. Fred Pescatore. Pescatore is a practicing physician in New York and is also the author of The Hamptons Diet, Thin for Good, and The A-List Diet. And during her tenure at the weekly glossy from 2003 to 2017, Abrahamson had his number memorized.

“We would email him photos and he would look at the photos and say, ‘She weighs 120 pounds’ or ‘Here she weighs 150, and here she weighs 135,’ ” says Abrahamson, who’s now a reporter at Today.com. “We didn’t think that this was crazy. It was just normal.”

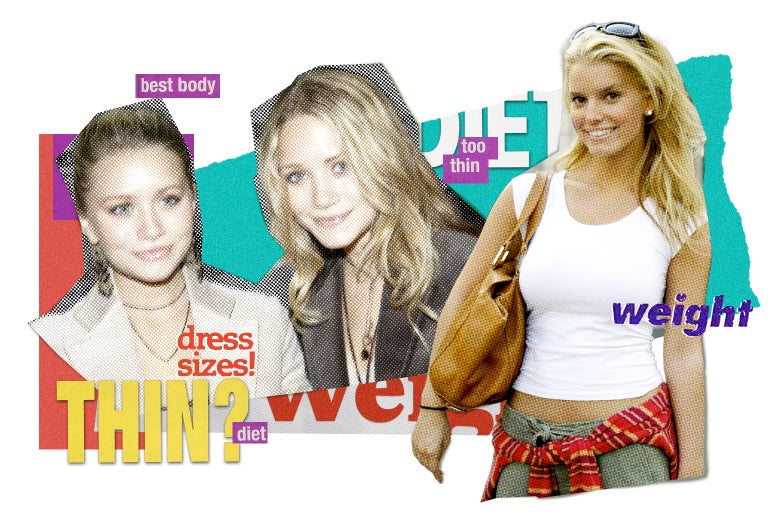

In the early aughts, objectifying bodies was a national pastime, and opportunities to do so were everywhere. Through the proliferation of tabloids, gossip blogs, and weekly celebrity news roundups and roasts on E!’s The Soup, consumers were encouraged to apply an overcritical eye toward the women they saw on the page and screen. It didn’t matter what a celebrity might say about their own body and their health—in the days before Instagram, and direct access to fans, magazine speculation about who had an eating disorder and why overpowered any statement a celebrity offered about their intake, metabolism, or genetic makeup. And if you were a celebrity, particularly one who was a woman, who wanted your weight to stay out of the gossip mill? Forget it. Celebrity bodies—and what they fed them—were the hottest stories.

“Issues about weight sold amazingly well,” says Nadia (not her real name), a former celebrity reporter and tabloid editor.* She got her start at In Touch Weekly back in the late 2000s and spoke to me on the condition of anonymity to protect her career. While giants like Entertainment Weekly and InStyle have recently gone digital only, in those days, print issues of magazines were sold at every drugstore and supermarket.

According to data supplied by the Alliance for Audited Media, at their peak in 2006, a single issue of Us Weekly or Life & Style sold an average of 992,238 and 720,616 copies respectively while In Touch topped off a year later with an average of 1,248,563.

“The pressure to come up with good headlines and stories was immense,” says Jared Shapiro, the managing director and founder of the Miami-based branding and marketing agency the Tag Experience. His résumé includes editorial director of Life & Style and In Touch, as well as assistant to glossy mag revolutionary Bonnie Fuller during her reign as editor in chief of Us Weekly back in 2002. Breaking down the numbers, he explained: If one headline resulted in a 20 percent bump in sales, that was roughly an additional $800,000 on top of the magazine’s average of $4 million per week (not including subscriptions). Which meant that if teasing weight and diet stories on the magazine cover or including coverage of a star’s “yo-yo” diet and “scary skinny” photos got people to stop at a newsstand and pick up a copy, editors would ride that strategy into the sunset.

We knew the super-skinny beauty standard was bad in the ’00s.There was no shortage of think pieces and insider testimonials about the dangers, with journalists pointing to people like Kate Bosworth, Kate Moss, Nicole Richie, Keira Knightley, Calista Flockhart, Angelina Jolie, and a bevy of other waifish favorites as products of an industry trend gone awry. Nonetheless, bloggers like Perez Hilton and Jared Eng of Just Jared, shock jock Howard Stern—who, in 2005, tricked Nicole Richie into being weighed on his program—and even Joan Rivers and her comedy apostles doubled down on their efforts to turn celebrity weight into a global conversation.

And tabloids led the charge. Some diet-centric pieces asked the stars directly about what they ate, printing food diaries with calorie counts alongside quotes from their trainers and stylists affirming their healthy lifestyle choices. But the predominant methodology was to assume, accuse, and smear. A weight change was never just a weight change; every pound lost was assigned a hypothesis whether it be a bad breakup, a drug habit, the quest for a “revenge body” so tight it would destroy an ex on impact, or a secret struggle with anorexia. Inversely, 10 pounds gained could turn a former beauty icon like Anna Nicole Smith or Britney Spears into an emblem of white trash and a cautionary tale of the perils of fame and excess.

Abrahamson remembers the intensity with which they tracked Jessica Simpson’s figure over the years, recounting an instance when she followed her to a Mexican restaurant in New York City, were handed the bill at the end of the evening from a source, and totaled the number of calories in a night’s worth of margaritas as evidence of the singer’s sloppy distress. (Last year, Simpson posted on Instagram about her struggles with alcoholism.) Shapiro contends that this kind of food tracking was partially a product of loyal sources all over the East and West coasts and sky-high magazine budgets. “If somebody told us that Justin Timberlake and Cameron Diaz were going to be at a restaurant at 7 o’clock, they were going to walk in at 7 o’clock,” he says, adding that he was providing a real example. “And guess who had the table next to them? We did.” (Nadia also mentioned that she’d be given a carte blanche to order anything she wanted while on a celebrity stakeout.)

While legitimate reporting could go into these pieces, the resulting stories were often a mix of cartoonish framing and cherry-picked “stats.” In 2006, Us Weekly published spreads with headlines like “How Much Do Stars Really Weigh?” and “Goalpost Gams!” Both displayed a lineup of celebrities with their estimated weights. The latter presented paparazzi style shots of women like Victoria Beckham, Ellen Pompeo, and Mary-Kate Olsen overlaid with clip art of a field goal stuck between their legs and a guess at the number of inches between their thighs. Explaining how the measurements of the stars were generated, Nadia said, “The editor would want the weight estimate as low as possible as a scare factor.” So if one nutritionist guessed a reasonable number, it would be up to the reporters to find another source who’d go on the record with a double-digit wager.

Other articles juxtaposed a star’s denial of disordered eating with anonymous sources “confirming” medical procedures, bouts of starvation, or drug use, plus assertions from experts that whatever the subject was doing just wasn’t right. Courtney Love and her team may have said she lost 44 pounds due to a change in diet and a new yoga regime—but an uncredited source provided the tip that a gastric bypass surgery was what really did the job. And even if a celebrity (or more often, their representation) refuted a reporter’s claims when approached for comment on a paparazzi photo or a tip-off about a carrot-a-day diet, the story would still run. Nadia explains that without the fear of widespread social media backlash, magazines confidently printed the sordid rumors anyway, simply weaving the rebuttal into the copy. Stylist Rachel Zoe and singer LeAnn Rimes may have protested accusations of anorexia, boasting fast metabolisms or good genes, but that wasn’t enough to stop gossipmongers and weekly entertainment rags from declaring a diagnosis.

The charges of anorexia were focused mainly on white stars, leaving women of color in a strange bind—Halle Berry, Angela Bassett, Salma Hayek, and Jennifer Lopez were frequently showcased as the healthy counterparts to the white women on the page, leaving little room for discussion of eating disorders among people of color. “There was definitely an issue with lack of diversity in the pages,” says Nadia. At the same time, Us Weekly’s bestselling issue ever featured a cover photo of Janet Jackson baring her abs and cleavage in a slinky two piece. “How I Got Thin” “60 Pounds in 4 Months!” blared the headline. The cover promised Jackson’s first interview on “her lifelong weight struggle,” and “Her daily menus and workout secrets.” A smaller photo under the caption showed a before photo of Jackson wearing oversize clothing. That June 5, 2006, issue sold 1,336,294 single copies.

Now, when articles broach topics like eating disorders, mental illness, and drug use, they are often accompanied by numbers for relevant helplines and links to resources for those who are struggling. Part of the shift was pressure from stars themselves: In 2007, Keira Knightley won a defamation lawsuit against the British rag Daily Mail for allegations that she had an eating disorder and that printed images of her in a bikini contributed to the death of a 19-year-old girl from anorexia. A year later, Lisa Marie Presley sued the Mail for asserting that she was developing an “unhealthy appetite,” forcing her to reveal that she was pregnant lest the rumors continue. Nadia notes that due to the growing presence of the body positivity movement and the overall shifts in how society views mental illness, there’s a greater emphasis within the media on avoiding triggers to protect the readers. (There’s also the risk of debilitating legal fees and drops in sales—or clicks—due to a public relations crisis.)

At least the editors of the ’00s say they are a little remorseful. “I would definitely say shame on editors and throw me in there if you want,” says Shapiro in regards to the presumptions the media made about a star’s body during the tabloids’ heydays. (Since 2008, Us Weekly, Life & Style, and In Touch have seen a continuous drop in sales. As of the latter half of 2021, the average single copy sales fell under 65,000 for each publication.) “There were different society views and expectations. We spoke about these subjects differently back then. Shame on anyone for accusing anyone of anorexia or bulimia.” He continues that while it may have been obvious when a star lost weight, “Who are you to say what that person is going through or struggling with mentally?”

Nadia agrees. “I feel bad about it, 100 percent,” she says. “I can’t imagine how difficult that is to have people scrutinizing your body on a global scale. It wasn’t right. It was just so normalized at the time even in the most mainstream publications.”

Their grip on society will certainly never be the same, which Abrahamson contends is a good thing. “I’m relieved in a way that the tabloids don’t have the reach they once did.”

Correction, July 6, 2022: This article originally misstated that “Nadia” is currently a tabloid editor.

Update, July 6, 2002: This article has been updated since publication.