A couple hours after Roe v. Wade was overturned, the Archdiocese of New York celebrated the retreat of the “culture of death.” But its triumphant statement came with a note of caution: “We still have a lot of work ahead of us in New York, as the loud, angry, potentially violent response of the pro-abortion movement makes clear.”

The allusion to potential violence from pro-choice activists may seem premature or recklessly dramatic to those not steeped in pro-life media.

After all, there are very few news reports of actual violence to support that claim. But for the past couple months—and, to a lesser extent, the past couple years—the Catholic right has been ramping up its warnings about “anti-Catholic bigotry,” mainly in response to instances of vandalism, tying graffiti to omens of bloodshed.

This has meant that the narrative about the end of Roe (even before it was overturned) has not simply been about a win at the Supreme Court, but of a religion under attack from violent and hateful radicals. “We seem to face growing hostility for putting our faith into action,” the archbishop of New York, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, wrote in a Fox News article published the night before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision that overturned Roe. The conservative political group CatholicVote.org issued a similar warning earlier that month: “Our sources tell us government officials are already warning Catholic dioceses: when and if Roe v. Wade is overturned, churches and pro-life support centers will be targeted for vandalism, violence, or worse.” (The conservative Catholic League took it one step further in a press release from May titled, “BIDEN CONDEMNS ATTACKS ON GAYS, NOT CATHOLICS.”)

It’s not untrue that the Catholic Church is intertwined with the end of Roe in the public’s mind. While the reality is that white evangelicals are the real drivers of the anti-abortion movement (polling has consistently shown that Catholics, unlike white evangelicals, are largely ambivalent about abortion), the anti-abortion movement was founded by the Catholic Church, which still provides its intellectual framework. There are the more visible elements too: the distinctly Catholic symbols that look good on protest signs or make for catchy chants, and the Catholic justices who struck down Roe.

But the very real history of ugly and violent anti-Catholic bigotry in the U.S., tied to its association with immigrants, makes some Catholics understandably worried about backlash. For older Catholics who remember now-antiquated prejudices, a radical group vowing to “burn the Eucharist” may seem to be tapping into a vein of real historical hatred.

This has not been lost on idealogues like Cardinal Dolan.

In a New York Post op-ed last year, in which he also referenced the 19th century anti-Catholic Know Nothing party, Cardinal Dolan described vandals who spray-painted “ACAB” on St. Patrick’s Cathedral as “pure bigots.” In an official statement on behalf of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the nonpartisan organization for all U.S. bishops, he called other instances of vandalism of churches “acts of hate.”

Have Anti-Catholic Hate Crimes Increased?

To be fair, anecdotally there does seem to have been an increase in vandalism on churches.

The USCCB started a running list of these instances in 2020, and according to its record-keeping, there were three instances in June and eight in May in which churches were defaced with explicitly pro-choice graffiti; the organization counted 20 cases overall in those two months in which church institutions were vandalized. (At the beginning of 2022, the USCCB called for federal funds to improve security measures at churches.)

But those numbers should be put into perspective. Almost all of the incidents were property crimes, and anti-Catholic hate crimes are generally around 1 percent of all hate crimes in the country—a blip compared with antisemitic crimes, per FBI data.

Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University–San Bernardino, said that he sees an increase in anti-Catholic incidents compared with previous periods, but it doesn’t rise to the level where it is out of sync with what’s happening more broadly.

“Anti-Catholic crime has gone up since 2020,” Levin said in a recent phone call, “but hate crime in general has gone up. When we have a very polarized and angry society, it’s true that violence begets violence. But it’s not necessarily evenly distributed.

“Yes, I’m concerned about churches,” he added, “but we’ve not yet seen anything other than a smattering, not something where we can determine a conclusion.”

According to Levin, violent action stemming from abortion-related activism has traditionally come from extreme anti-abortion activists or the far right. “The movements behind women’s rights have been generally textbook with regard to using the processes and institutions of a pluralistic democracy to attain their ends,” he said. “What’s different this time is it’s more than a speed bump—this will be regarded as a tectonic shift. But the history and the subculture of women’s rights just has generally not included that deep well of violent aggressive action.”

He acknowledged that the pro-choice movement, given its breadth and size, would likely engender some extremist action. But he doubted it would be significantly violent. “When you remove the machismo out of extremism, you remove a lot of extremism out of extremism,” he said.

One radical group, known as Jane’s Revenge, has gotten a lot of attention for claiming responsibility for some firebombings of pro-life Christian pregnancy centers as well as threatening graffiti found on churches with phrases like “if abortions aren’t safe, neither are you.”

But it’s unclear if Jane’s Revenge is a real organized group, or if it’s genuinely a violent threat. (No one has been injured in any of the attacks.) The Department of Homeland Security has called Jane’s Revenge a “network of loosely affiliated suspected violent extremists.” White House assistant press secretary Alexandra LaManna condemned Jane’s Revenge’s actions in a statement to the Daily Wire: “We should all agree that actions like this are completely unacceptable regardless of our politics.”.

But the big, fearful event amplified by prominent conservatives—a “night of rage” over the Dobbs ruling, supposedly called for by Jane’s Revenge—never materialized. And though fires at several anti-abortion pregnancy centers are being investigated as suspected arson attacks, the main problem churches have faced is aggressively worded graffiti.

“The mere fact that we have stereotyping and derisive language around Catholicism and other organized religion and their role with respect to abortion creates a heightened risk,” Levin said. He acknowledged that the idea of Jane’s Revenge could be extremely worrying to churches. But otherwise, “we’re not really seeing the calls to violence that we saw with other controversies.”

Is It Roe-Related?

There’s another important piece of context to the “surge of anti-Catholic attacks” narrative: These talking points have been in use since 2020.

Many cases of vandalism haven’t been related to Roe at all.

The USCCB began tracking attacks on churches after two caught fire in separate incidents on July 11, 2020. In both cases, the motive remains unclear. In the first, in Florida, the suspect had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and had not been taking his medication. In the second, in California, the suspect had a history of arson-related arrests. That church had also, incidentally, been established by St. Junípero Serra, an 18th century Spanish missionary to California seen by many Indigenous Americans as a coercive and cruel colonialist. That summer, statues of Serra were toppled elsewhere, and missions founded by the saint were vandalized.

This tracks with other protest actions taken after the murder of George Floyd by police. But that is not how some Catholic leaders talked about it.

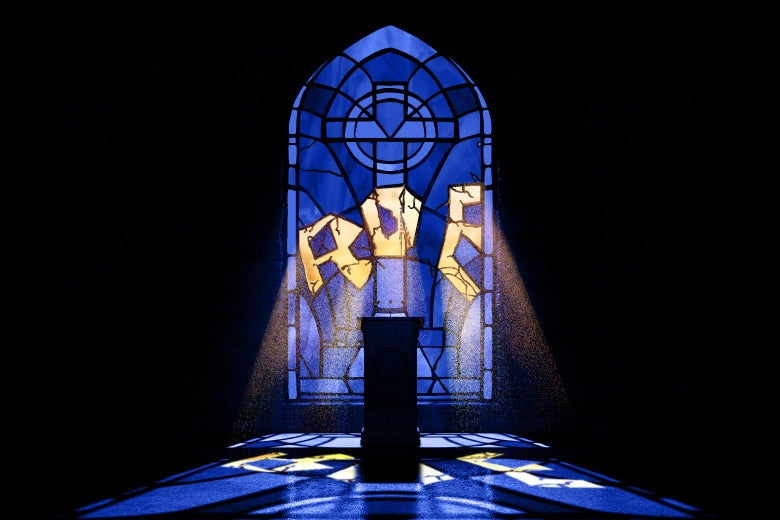

“The underlying motive of these sacrilegious attacks is clear: to intimidate and instill fear in the hearts of those who worship Christ,” the Archdiocese of Hartford, Connecticut, said in a statement to the Wall Street Journal that summer. (Anarchist and satanic symbols had been painted on a New Haven church’s door.) “However, our cherished Catholic faith has survived for 2,000 years in the faces of many different oppressors, and it is not about to yield now.”

The following summer, in Canada, unmarked graves were found at residential schools for Indigenous children that had been operated by Catholic orders or dioceses. Several churches in Canada were vandalized or burned—enough to count as a “disturbing” and “significant” number, according to Brian Levin. But it is unlikely that that violence had anything to do with Roe.

In a count that goes back to May 2020, the USCCB has noted 144 incidents of arson, vandalism, and destruction on Catholic churches in the U.S. For anyone who has been paying attention to the conversation on the Catholic pro-life right, it is clear that the victimhood identification following these instances is not new or a real response to Dobbs; it has been building for years.

And conservative Catholic media outlets such as EWTN have been playing it up. As have other power players in the Catholic world, sometimes with agendas that might be hidden to the average observer.

In an op-ed published in the Washington Post last year, two Catholic writers addressed an incident in which the words “Satan lives here” were spray-painted on a Denver cathedral, in large part because of the church’s opposition to abortion. (A 26-year-old woman was charged with a hate crime. The suspect grew up Catholic; claims of anti-Catholic prejudice rarely distinguish between those committed by outsiders and those committed by former members of the church.)

“You would likely have to go back to the early 20th or late 19th centuries, when an influx of Catholic immigrants challenged a mostly Protestant culture, to find so much public antagonism toward the Catholic Church,” the authors of the op-ed wrote.

But the writers, Archbishop Samuel J. Aquila of Denver and Catholic philanthropist Tim Busch, aren’t just regular Catholics fighting for their rights to practice religion without fear. They are board member and the chairman, respectively, of the Napa Institute, a network for wealthy conservative Catholics who are pushing culture war issues in elite Catholic institutions.

They did not mention that at a Napa event, one of them once gave a speech attacking “the biggest catastrophe” of abortion in front of an audience that included Justice Sam Alito, or that one of the organization’s major donors and former board members is Leonard Leo, the man often credited with shaping the court into one that could overturn Roe. Instead, Aquila and Busch made a reasonable-sounding plea for the kind of pluralism they would deny to others.

“Let’s remember that all of us have a right to our own beliefs and a duty to accept that others have the same right,” they wrote. “If we do not, things will get far worse than seeing ‘Satan lives here’ spray-painted on a cathedral door.”