In the supernatural horror film The Black Phone, a new box-office hit, a sadistic child abductor and killer known as “the Grabber” (Ethan Hawke) terrorizes a quaint suburb with a theatrical flair and a van filled with black balloons. The Grabber is on the prowl in late 1970s Colorado, and he preys on “all-American” boys, luring them into his black van before locking them in a dark, austere basement, playing a “game” with them, and murdering them. It appears that no boy is safe—not Bruce Yamada, the popular and handsome baseball player; not an unsuspecting paperboy named Billy; not the tough yet kindhearted bully slayer Robin Arellano; and not Robin’s meek friend and tutor Finney Shaw (Mason Thames). One Friday afternoon, the Grabber snatches Finney on a quiet street as the youngster walks home from school, and the film kicks fully into its queasy exploitation of the panics of the late 1970s, a moment fraught with anxieties about serial killers and violent crime. We didn’t have milk carton ads yet—although they appear anachronistically in the film’s opening credits—but “stranger danger” began here, and The Black Phone revels in the throwback nightmare.

The Grabber is sadistic, vaguely satanic, and coded as queer, with a predilection for fair-skinned teenage boys. The character distills and expresses many of the fears that animated white suburban America in the late ’70s and into the 1980s: Widespread concerns about homosexual depravity and boyhood innocence transformed horrific but rare incidents such as the Etan Patz abduction and the Adam Walsh kidnapping and murder into major events with national resonance. The Black Phone draws on this history, endowing its young protagonists Finney and Gwen Shaw (Madeleine McGraw) with the strength of the Grabber’s previous young male victims, who communicate with Finney through a mysterious, magical black phone. The movie never quite depicts sexual abuse, and it confines the killer’s queerness to coy hints. But it clearly taps into deeply rooted moral panics concerning child sexual exploitation, “grooming,” and homosexual predation—panics that are, not incidentally, very much ongoing today. Though set nearly 40 years ago, The Black Phone arrives at a peculiar moment to reflect (and perhaps shape) America’s present anxieties about real and imagined threats to children.

In the movie—directed by horror veteran Scott Derrickson (Sinister) and adapted from a 2004 short story by Joe Hill—the Grabber efficiently kidnaps and kills his other victims, but Finney’s case presents certain challenges. For one, the Grabber’s brother Max, a true crime and cocaine aficionado, is visiting, preventing the Grabber from operating as brazenly as he normally does. And Finney can hear the voices of the Grabber’s previous victims, who guide him in the hope that he’ll avoid their fate. They identify potential escape routes and traps set by the Grabber. When the Grabber leaves the basement door ajar, Finney sees a way out, but one of his guides (speaking through the black phone) begs him not to take the bait: The Grabber is waiting—half-naked, seated, whip in hand, prepared to “punish” his young victim. Finney’s refusal to play “naughty boy,” the Grabber’s game, complicates the kidnapper’s wicked plan.

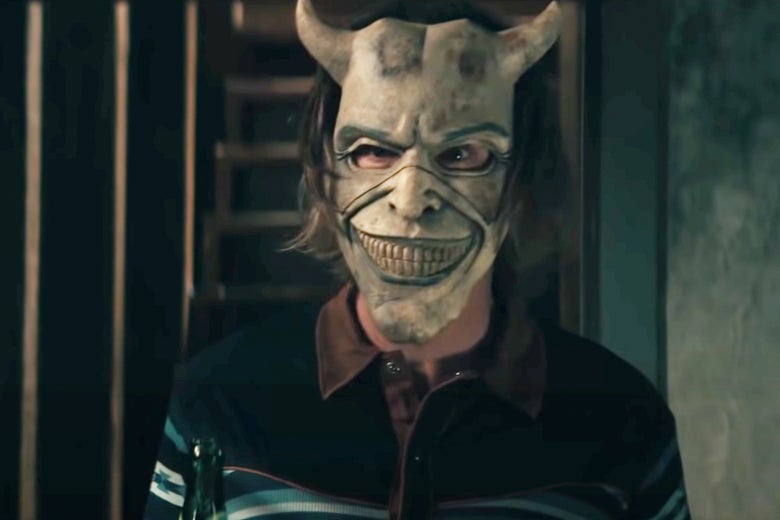

Though The Black Phone tries to avoid making it explicit, The Grabber is heavily coded in this moment as not just a kidnapper and murderer but also a sexual predator, presumably fueled by pedophilic desire. Hawke’s Grabber is whimsical, with a penchant for magic and theatrics. He dons white stage makeup, terrifying adjustable masks, garish rings, and a cape and top hat at times. He speaks in dulcet, high-pitched tones, unless he’s threatening or abusing a victim, in which case his voice deepens and grows rougher.

With his capricious swings between childishness and aggression, Hawke’s portrayal gestures to some of the most notorious mass killers of the 1970s, a decade in which researchers, law enforcement officials, and everyday Americans became increasingly interested in the phenomena of serial rape and murder. In 1972, the Federal Bureau of Investigation established its Behavioral Science Unit, dedicated to studying and profiling serial rapists and killers such as Dean Corll (known as “the Candy Man” because he gave children free candy from his family’s candy factory) and the infamous clown John Wayne Gacy. (The Grabber is a “part-time clown” in Hill’s short story, but in the movie, he’s a magician.) In the late 1970s and into the 1980s, Jeffrey Dahmer and Wayne Williams—who, like Gacy and Corll, targeted boys and young men from marginalized communities—struck fear into the hearts of millions. The gruesome details circulated in the nightly news and in true crime literature for years to come. But just as significant as the details shared in the media were the aspects of these crimes that remained unspoken.

The filmmakers behind The Black Phone leave us to learn of the Grabber’s worst deeds through the voices of his past victims. The film, again, doesn’t explicitly state that the Grabber’s victims were sexually assaulted, but it calls upon the audience to fill in those details. The ghost victims describe being beaten, and the audience sees the Grabber sitting menacingly, shirtless, with belt in hand. One victim tells Finney over the phone that he lost his innocence amid abuse that was far worse than the belt-beating. The Grabber also “reassures” Finney with the chilling remark “I’m not going to make you do anything you won’t like.” We understand Finney’s kidnapping is only the beginning of the harm to come. The details of the Grabber’s queerness—his light, airy voice, flair for theatrics, immaturity, and isolation, interrupted only by the presence of his brother during Finney’s captivity—provide all that an audience steeped in decades of queer panic needs to fill in those blanks.

This invitation to imagine the specific threats that deviant people pose, particularly to children, was a key feature of the “stranger danger” discourse of the 1980s and 1990s. Bereaved parents, the media, and the “moral entrepreneurs” who sought to profit from a growing child safety regime often promulgated conspiracy theories about child sex trafficking rings, stories of gruesome experiments conducted on children, and tales of the satanic ritual abuse of kids. The McMartin preschool saga involved wild, unsubstantiated accounts of underground tunnels, animal sacrifice, and supernatural activity. During a 1984 U.S. Senate hearing, the mother of missing paperboy Johnny Gosch insisted that the North American Man/Boy Love Association (and possibly other “homosexual groups”) had kidnapped her son and incorporated him into their “organized pedophilia operations.” For his part, grieving father and longtime America’s Most Wanted host John Walsh often marshaled spectacular (or imagined) cases of child exploitation to advance his tough-on-crime agenda. A 1984 Chicago Tribune profile detailed Walsh’s breakfast with a friend, the parent of an 18-month-old daughter: “Just envision it for a minute, a 200-pound man raping your daughter,” he told his friend. “I mean it. Envision it. It could happen.”

These elaborate, concocted visions of child abuse persist in our growing contemporary queer panic, with clear evidence in today’s Florida and elsewhere. Without evidence of any actual threat, concerned parents are instead called to imagine the harms queer and trans teachers, coaches, and students might perpetrate upon “innocent” children. Because these are imagined threats rather than substantive ones, it is not surprising that these anxieties have coalesced around vague notions of “grooming” and recruiting, which were central to the anti-gay campaigns waged by Anita Bryant and others in the late 1970s, the same moment in which Finney gets taken by the Grabber. Bryant infamously claimed that gay men “must recruit” because they could not reproduce.

So is The Black Phone simply playing on these echoes of panics past and present, or using them to stoke more terror? Doesn’t a movie like this feel bizarrely regressive in 2022? Yes and no. The Black Phone suggests that just as harmful as the imagined threats posed by queer boogiemen are the very real threats within the institutions thought to keep children safe. Abusive parents, school bullies, and incompetent police officers endanger even those children not taken by the Grabber. North Denver’s adults fail to mobilize to protect the town’s children, who are consistently seen walking and biking alone, vulnerable to predation. And in one of the most disturbing scenes in the film, Finney and Gwen’s alcoholic widower father, Terrence, brutally beats Gwen with a belt as Finney looks on helplessly. Ultimately, it is not the adults who rescue Finney but other kids: It’s his sister, Gwen, whose clairvoyance provides vital clues for the bumbling detectives, the ghost children who guide Finney with the help of the black phone, and Finney himself who musters the courage to fight back.

While right-wing politicians and moral entrepreneurs continue to incite their forever panics, the reality of child endangerment is far less sensational. The perils confronting the nation’s children rarely take the form of a sinister, queer, masked predator prowling suburban streets for his next victim. Young people are far more likely to be abused or neglected by a parent, family member, peer, or authority figure than a cartoonish villain like the Grabber. These quotidian threats seldom capture headlines or provide fodder for horror films like The Black Phone. But they are more insidious and more terrifying than anything a horror movie can conjure.